Submitted by tomrue on

OPINION

By Tom Rue

Disparate Treatment in Local Special Education

Among the most interesting things about a report of a study on disparities in the education of ethnic minority students (specifically Latino and Black) youth receive in Monticello schools, compared to White students in the same district, published last month on the website of Monticello Central School District, is that the study was undertaken in the first place.

When I asked Monticello schools' superintendent Pat Michel how the study by the Metropolitan Center for Urban Education occurred - whether the district was selected for study or if the school board requested it, Dr. Michel replied: "We reached out to them. This is a very important issue to us and we want to address it. I am lucky because I have a board of education that wants all students to succeed."

Secondly, the fact that it has been published prominently on the base page of the district's website also speaks well for the the seriousness with which superintendent Pat Michel and the board of education are committed to making systemic changes.

The report details at length the existence of significant disparities in the way MCSD utilizes Special Education for Black and Latino youth, particularly males, in relation to other students. Simply put, minority youth (and more so minority boys) are more likely to be classified as Learning Disabled by the Committee on Special Education; and of those who are classified, the same subgroups are more likely to be placed in IEP learning tracks rather than being given what the authors describe as less stigmatizing 504 accommodations [*].

Learning to 'Keep Coming Back' Despite Adversity or Setbacks

The authors noted that something they called "academic resilience" was the best predicter of whether a student will perform well in school. "Academic Resilience is the extent to which students perceive themselves as having personality characteristics related to academic success even when faced with adversity.

These components include persistence, resourcefulness, self-confidence, and sociability," they explained.

"Resilience" is the ability to return after a setback and keep trying. Parents, community leaders, and educators should all take note of this.

A large body of psychological research identifies to resilience as one of the greatest protectors against Major Depression and Anxiety Disorders. Resilience has been found to be the the psychological best antidote to many of life's challenges, ranging from stress in the workplace to surviving cancer [Google Scholar for citations].

A second barrier to learning for minority students is negative expectations by students themselves, by their teachers, and presumably also by their parents about their ability to succeed in school and go on to college. They referred to these reduced expectations as "stereotype threat", which they said "measures the extent to which indivudals are vulnerable to negative stereotypes about the academic performance of one's ethnic or gender group.

Students who internalize these belief that they are likely to fail will, in fact, do less well in school. How does this happen?

Consider the statements of Monticello High School students themselves, quoted in the report from interviews conducted during the study:

"In general, the research shows... that students who reported being more challenged in their courswork - typically honors students who tend to be White females - are more likely to have higher grades than their peers."Students expressed that teachers had different expectations for different students. Notably, students in honors classes expressed a more positive scholarly experience and perceived teachers as available for help. For example, one female honors student said, "They [teachers] love what they're teaching and they connect with you on a personal level, unlike the rest of the teachers."

Yet, many students suggested that teachers don't share the same expectation of achievement for all students. For example an honors student observed that, "Some teachers don't engage the whole class and maybe a certain set of students, which leaves other students in the class to wander off or travel off and once they're not paying attention, they're obviously not taking anything in. And then obviously you get more and more lost. You want to do the work, it's not going to happen, because you have no idea how to do it. So, some teachers allow students to get a little bit too far off the trail because they try to get them back on where you can't."

Students stated that some teachers had generally high expecations, while others did not. Often this affected student performance. "I get really good grades; I'm on honor roll and stuff, but I felt like this year our teachers just stopped caring," reported an advanced-level student in focus group.

Another responded, "In elementary, also, I definitely felt like I got pushed more than I do in high school." Students who identified faculty members as 'having high expectations' also considered them as 'favorite' teachers. In addition, students reported that factulty had higher expectations for some students and lower expectations for others. One student who does not attend honors courses remarked, "I think there's a lot of favoritism in this school."

Clearly, the statements quoted above illustrate that there are some excellent teachers at Monticello High School, just as there are some who stand in contrast and who are pointed the way to professional development.

The bottom line is, children give us what we as adults expect from them.

If we expect excellence, and consistently give them the message that they are winners and likely to succeed, they are much more likely to be excellent. If we expect mediocrity, whether because of racial or ethnic stereotypes or because of past experience with a particular child, that is probably what they will provide.

Research Elsewhere By The Same Authors

Another report by some of the same authors of the Monticello study compared several inner-city public schools as they did in the Monticello report, emphasized "the importance of knowing the lived experience of the boys they are serving."

A second need noted in this report was a "dearth of positive male role models for their students," a need which the authors hoped could be met by urging teachers "to readily embrace this role for their students."

Toward a more gender specific approach to education, the writers cited a need to change "notions of masculinity", as well as of what it means to be a Black or Latino man. "In other words, the boys are being taught not to be the kind of man stereotypically associated with the communities poor Black and Latino males often come from," they wrote.

Of the schools studied, Fergus and his fellow researchers said, "Black culture, these administrators reported, inhibit the boys’ abilities to move forward educationally. In addition, the boys are viewed as susceptible to peer and cultural pressures that tell them, according to the principal, “It’s not cool to be smart.”

In this report, the authors cited a need to raise expectations and making the schools' curriculum and instruction more relevant to students' lives.

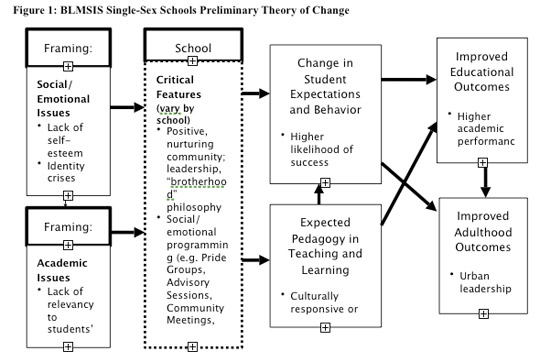

Furgus, et al. gave the following diagram of their theory of how to bring about systemic change through single-sex schools, which most careful readers will most likely agree can be applied in most any school in need of cultural reform:

Another study, also written by Margary Martin suggest "that supportive school-based relationships strongly contribute to both the academic engagement and the school performance of the participants."

Clearly, Monticello is not about to begin segregating boys from girls. However, the point made about the need for boys to re-learn what it means to be masculine is important to note.

Boys need to believe that doing well in school is "cool". Girls seem to get this, though historically this has not always been true.

These findings give parents in the Monticello community, as well as professional educators, some useful food for some self-reflective thought, if they will accept it, not view the NYU report as simply critical of local educators, for it is not.

Related Links

- Margary Martin, Tonya Leslie, Maureen Manion-Leone, and Edward Fergus (2010). Monticello School District: Achievement Gap - Exploratory Assessment, Margary Martin, Tonya Leslie, Maureen Manion-Leone, and Dr. Edward Fergus (2010), Metropolitan Urban Center for Urban Education, NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, released July 21, 2010. [Also reported in Monticello minority students lag behind, study finds - Fewer heading for graduation, survey reveals, The Times Herald-Record, August 16, 2010.]

- Edward Fergus, Katie Sciurba, Margary Martin, and Pedro Noguera (2009). Single-Sex Schools for Black and Latino Boys: An Intervention in Search of Theory, In Motion Magazine October 31.

- Carola Suarez-Orozco , Allyson Pimentel & Margary Martin (2009). The Significance of Relationships: Academic Engagement and Achievement Among Newcomer Immigrant Youth, Teachers College Record Volume 111 Number 3, 2009, p. 712-749.

- tomrue's blog

- Log in to post comments